And now the STORM-BLAST came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with his o'ertaking wings,

And chased us south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yelling blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe,

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

– from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1798)

My right shoulder slammed into the corner of a picture frame welded to the wall. That was going to be a bruise. I regained my balance and used the falling of the ship’s prow to skitter forward a dozen steps before catching my left hip on the handrail that I should have been holding. In all my excitement and careful wardrobe planning for this Antarctic cruise, I hadn’t thought about the 2-day crossing of the Drake Passage. This treacherous stretch of water between South America’s Cape Horn and the Antarctic Peninsula — where the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans meet in a frenzied swirl — deserves its reputation: it was foolish of me to wear 3-inch heels to dinner.

My voyage had started inauspiciously when I’d stepped off the shuttle bus that morning from the Buenos Aires hotel to the airport and my husband asked me, “Where’s the carryon?” The subsequent hoop-jumping performed by the Seabourn personnel was nothing short of miraculous. We had to continue on our scheduled flight, but they located the suitcase containing all our toiletries, makeup, pajamas, books and jewelry in the vacated hotel room, flew the bag 2,000 miles south to Ushuaia, Argentina with someone who had not packed it (I think that’s against the rules…?), and delivered it to our cabin before the ship left the harbor. Their patience and good humor continued unabated even when I lost my room key one hour after cast-off and they had to print me a new one. I heartily recommend Seabourn for perfect customer service and am happy to have provided these opportunities for them to shine.

Pitching and rolling over the Drake, I lay in bed that night listening to the popping and creaking of the ship, so loud that my earplugs could not block the sound, and imagined Sir Francis Drake in his 16th century galleon first sighting these waters. I channeled his crew’s terror as the violent waves – then levitating me over my bed – tossed their ship off course in 1578, following their successful westward navigation of the Strait of Magellan. They saw the end of the continent, made a note in the log, and scurried up the west coast of South America.

At the bottom of the Drake Passage lie approximately 800 shipwrecks and the remains of an estimated 20,000 sailors who attempted these waters in their wooden ships. I thought of those scurvy-plagued men as the bowl of fruit on our cabin’s coffee table slid to the floor with a thud, and I heard a bottle of unsecured something hit the floor of the bathroom. I knew going into this that Seabourn would provide the illusion of adventure without any of the danger in our state-of-the-art, 6-month-old ship. It was built to PC6 Polar Class standards, which sounds really safe, right? The rising of the ship pressed me into the bed before dropping away. I fell back into the mattress and experienced one of those come-to-Jesus moments brought on by air turbulence and other bewildering threats. “Some will trust in captains and some will trust in PC6 Polar Class ships, but we trust in the name of the Lord our God.” The original verse has something to do with horses and chariots, but the reminder of who’s in charge is the same, and I finally fell asleep.

The next evening before dinner, we sighted our first iceberg. It stood like a white oil rig in the distance, alone in 360º of water. My family and I heard about it from a fellow passenger and ran down the hallway, bouncing from wall to wall, toward the Bow Lounge for an unobstructed view. Enjoying our excitement, a member of the housekeeping crew — Anya from Moldova — said, “Dat is nothing! You vill not belief the icebergs you vill see this veek!” Even if contemptible, it was our first glimpse of the isolation, raw power, and vastness of the world we would shortly enter.

No one could mistake me for an adventurer — I’ve had to grudgingly accept that I’m a bit delicate and accident-prone — so it is with great pride that I announce my discovery: I have an iron stomach. My husband — the stalwart outdoorsman — spent the ocean crossing in the bed seasick while I explored the ship, read and wrote, and ate heartily. Even my teenage children were a bit squeamish. Hah!

Our second day at sea brought great news: the 10-foot swells had carried us south more quickly than expected, and we would shortly disembark for a bonus, unplanned visit to the South Shetland Islands. There are no docks in those regions — all of our landings would take place via zodiac raft. We had already received our expedition thermal coats — colored international orange so no tourist would be left behind — and had been fitted for our waterproof boots, stored in our cubby on the landing deck. Even my son’s size 16 feet caused no crisis as the crew presented him with the one enormous pair they kept on hand for that rare exigency.

Before our landing group was called, the children gathered in our cabin for the gear-check that would be our daily routine that week. Beanie? Check. Two thermal base layers? Check. Puffer jacket and waterproof shell? Check. Check. Waterproof ski pants? Two pairs of socks? Ski gloves? Glacier glasses? Camera? Binoculars? Check. Check. Check. You forgot your lifejacket! Run back and get it. Do you have your key card? Got it. Ready?

Lifejackets secured “like a warm hug” as instructed, the four of us proceeded to the boot room on the landing deck, our nylon ski pants zip-zipping in rhythm as we walked with purpose toward our adventure, nerves jangling with excitement at the inherent danger. Our exploit suffered a slight re-imagining as we passed fellow guests returning from their earlier-scheduled landing. Their red-chapped cheeks, wide smiles and steaming cups of hot chocolate suggested a Disneyfied experience, like the submarine 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride from my youth. (Upon reflection, that ride was one of my favorites.)

Ski pants pulled over waterproof boots, we joined the line of orange jackets — our fellow guests unrecognizable under their balaclavas and ski goggles. Everyone presented his key card that was scanned by the staff — and would be scanned again upon re-embarkation (no tourist left behind) — and proceeded down the stairs to the hatch opened just above ocean level. Two Filipino sailors secured the zodiac to the ship with a line in one hand while offering a sailor’s wrist-to-wrist grip with the other. One by one, we grasped the sailors’ arms, stepped from the ship to the pitching zodiac, and obeyed the “sit and slide” command from our expedition driver. No walking on the zodiac ever. Sit on the rubber-tube edge, and hold onto the rope. Do not stand to take a picture unless you receive express permission. Do not drop your belongings over the side — we must preserve the natural purity of this pristine environment (never mind the loss of the item).

We bumped over the water of Half Moon Bay toward the crescent island where the nose of our zodiac crunched onto the pebbly shore and our driver cut the engine. One by one, we slid to the front and swung our heavy, knee-high boots over the side into the shin-deep water. We clambered up the black sand beach to the ridge of Half Moon Island — the exposed rim of a dormant, submerged volcano — and saw a neighboring island across a narrow strait, rising into the clouds.

The expedition crew had gone ahead of us as they would at every site, checking landing conditions, plotting out a safe trail away from crevasses, finding noteworthy wildlife, and marking forbidden zones where tourists must not tread. Seabourn is a member of IAATO, an unwieldy acronym that stands for International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. In short, it means that they agree to treat Nature like a brittle work of art that must not be touched. I got the impression that if you traveled with a non-IAATO company, you could do whatever you wanted, within reason: one of my friends who has visited the White Continent reported sliding down a snowy hill with the penguins. Not so on our trip. The following is a sampling of the rules of conduct for an IAATO tourist:

Stay 5 meters away from all wildlife at all times.

Take nothing — not even a pebble, certainly not a bone or an eggshell — from any landing site.

Do not touch, kneel, or lean on any surface. Remain standing at all times. (This one has to do with not picking up E.Coli from penguin guano — which is surprisingly ubiquitous — and bringing it back to the ship, a rule that has my allegiance.)

Give right-of-way to penguins traveling to and from the water on their little trails (called highways).

Do not go off the human trail scouted and marked by the guides.

Have fun!

My daughter was incredulous — her visions of snowball fights and building snowmen on Antarctica were dashed. I, too, was tempted to grouse about these restrictions — but soon reflected that the penguin guano sprayed on almost every surface was too disgusting for me to want to touch much of anything and that the sights seen on the marked trail were completely unprecedented in my life. What could I complain about missing? True, I would be robbed of the story of falling into a crevasse and having to be rescued — another opportunity for the Seabourn crew to show its worth — and I wouldn’t get to bring Antarctic souvenirs in the form of rocks, fossils, and bones to my friends as I’d hoped (sorry, y’all). But on the whole, I recommend traveling with a team that takes its vocation seriously.

At Half Moon Island, a biologist showed us the remains of a whale, beached in some distant age, with only a few of its half-buried ribs curving toward the sky. A chin-strap penguin wandered nearby, curious about the visitors, before continuing to the water to hunt for krill. The slowly desiccating carcass of a 6-foot long seal lay along the trail, marked off limits. (Did the crew think we would want to touch it?) Further up the ridge, a geologist discussed the volcanic nature of the rocks and pointed out the only flora in these parts: a smear of orange lichen on a boulder and a spot of green moss, wet with melting snow in the summer sun.

The balmy 0ºC summer weather created quite the beach culture for a community of chinstraps. Hundreds of them squawked happily at one another on the rocks while tending their eggs, soon to hatch, and waddled to and from the shore for a bath or a snack. Watching these animals look back at us from their natural habitat — not protected or fed by zookeepers — was disorienting. I had the impression they were saying to one another, “Give the orange creatures the right of way — stay 10 penguin lengths away at all times — don’t pick up any of their nasty germs.”

When the guano stench became too strong, we made our way back to the zodiac, pausing to view an open and empty eggshell — evidence of a hatched chick, we thought at the time. The blue skies and gentle wind had given us a happy view of penguin existence — a fiction that later, harsher days would correct.

The next morning — New Year’s Eve — began with the dulcet Italian tones of the expedition leader awakening us over the loudspeaker at 6:30 a.m. We had arrived at Devil’s Island in Erebus and Terror Gulf — so named for the first ships to navigate those waters, not some horrifying mishap. I looked out the cabin window across the water at the looming volcanic mountain, seemingly carved from a block of dark chocolate. At the base of the mountain, looking like dusty sugar bloom, nested tens of thousands of penguins.

Repeating yesterday’s equipment check, we soon found ourselves back on land, following the orange coats in front of us toward the penguin colony while a line of penguins followed the black coats in front of them toward the water. We passed a group of earlier orange coats on their way back to the zodiacs, and I toyed with disappointment that this prescribed tour would prevent anything unexpected from happening — when my gaze alighted on a fellow traveler. His thermal and waterproof gear stripped off, he stood in front of the penguins, posing for a picture, wearing a tuxedo. Now that was unexpected.

His levity banished my adventurous-explorer illusion, and I recalled that people like me (I?) don’t go to Antarctica without extreme safety measures, gourmet meals, and those 3-inch heels.

With reality embraced and enthusiasm renewed, I whipped out my iPhone to take pictures as one of the scientists exclaimed that these Gentoo penguins’ eggs had hatched! Grey, fluffy babies peeked from under their parents’ heavy bottoms, their little beaks opening in hunger. Another chick’s head had disappeared inside its parent’s open beak where it ate its coveted meal of regurgitated krill — unwelcome information provided by our biologist. The nestlings were tiny and vulnerable in this freezing weather, prey not just to the elements but to attacks from the sky, where hungry skuas circled like vultures.

Suddenly — as if we were a National Geographic team that had waited for hours — we witnessed the circle of life in action. A skua dived for a nest and flew toward the beach with a penguin chick in its beak. The adult penguins squawked in protest, and those on the beach charged the skua, chasing it away from the bleeding nestling lying on the shore. Another penguin stood over the baby, nuzzling it with its beak, but there was nothing to be done. The penguin wandered away, and the skua returned to enjoy its meal in peace — as we tourists watched in outrage at this patent injustice. The strong preying on the weak! There should be laws against such things!

Penguins are not people, and skuas have to eat, too, I reflected as we returned to the ship, proud capturers of real-life nature photography.

The next few days led to more meditations on life and death, thoughts I had not anticipated on my cruise. On D’Hainaut Island, we paused to watch 9-ft leopard seals sprawled on a rock, molting and slapping their itchy backs with awkward fins, while penguins — seals’ favorite snack — wandered close by. Lethal in the water, the slug-like seals posed no threat on land, and the penguins waddled on, oblivious to slumbering death. Another penguin later in the week had to be more philosophical — off our starboard bow, killer whales tossed him back and forth like a beach ball in the deep waters of the Gerlache Strait. Perhaps it was playing dead as penguins will do to lose their predator’s interest — but that particular penguin did not seem likely to evade death much longer.

Another day, in front of an abandoned, hundred-and-fifty-year-old whaling boat, we ruminated on the ephemerality of life and wondered about the man who had been here — so important to someone at some time, and now completely forgotten by everyone.

But the most profound of all the sights in Antarctica — that still fill me with awe — were the icebergs. They came in all shapes and heights, some flat as a table, going on for half a mile, others peaked fifteen stories high like a mountain. Some had jagged break patterns from a violent past. Others were rounded and smooth, licked clean by the water. There were shiny ones and blue ones and icebergs that were filthy with dirt — they had broken from the edge or bottom of a glacier and carried the mountain’s soil, filled with nutrients, out to sea. Every iceberg was unique, the product of some unknown past, and amazed me with its beauty.

On New Year’s Day, my family had an opportunity to view them from sea level as we joined a kayaking group in Hope Bay, the body of water at the very tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Let me not gloss over the fact that I had never sat in a kayak before and had a few questions. I entertained concerns about the upper body strength required to propel this craft (I can barely do three push ups and have never accomplished a pull up in my life); the possibility of flipping and, perhaps, remaining upside down in the frigid waters; and the advisability of being paired with my teenage son who might or might not share my concerns. My 14-year-old daughter told me later that she had been worried about her first trip in a kayak, as well, but when she saw me determinedly lower myself from the zodiac into the sturdy plastic boat, she thought, “Oh, if Mom can do it, no problem.”

Per usual on this trip, there was nothing to worry about. I quickly gained confidence and plotted my voyage toward a particularly beautiful iceberg where penguins sat cleaning themselves under a blue sky. Giving directions to my son (the engine of this craft who sat behind me), I was suddenly foiled by our guide’s safety instructions: “Stay as far away from an iceberg as it is tall.”

This restriction met with a chorus of whines. “Why?!”

Because, supposedly, an iceberg’s buoyancy is constantly changing as the underside slowly melts in the water. At any second, it could suddenly flip over and kill you — remember their proverbial enormity underneath. Besides that danger, the larger ones could unexpectedly calve, releasing a huge chunk that could fall over — and, also, kill you. As the adventurous spirit grew in me, those catastrophes seemed highly unlikely and well worth the chance to get closer to one of these natural works of art.

Just as I considered how close I could get without the expedition leader’s objecting, we all heard a resounding crack of thunder. The kayak rocked dangerously as my son and I turned back and forth looking for the source, the sound echoing off the surrounding mountains under the perfectly clear sky. “There!” someone shouted, pointing at a puff of snow rising in the air 500 yards across the bay. We watched in amazement as a colossal iceberg broke apart, dropping a chunk half the size of our ship into the water. Visions of tsunamis occurred to me in my little kayak, but by the time the wave reached us, we merely bobbed up and down. “And that is why we stay away from the icebergs,” our leader said. Point taken. We paddled around the bay, admired the massive formations from afar, and had enough collisions with brash ice — floating chunks of ice that could put a hole in your plastic kayak — to concern me about my son’s driving.

Though protected from actual deadly peril, we could still engage in mild risk. A couple days later, we entered Paradise Harbour and found a patch of water free of brash ice for the promised Polar Plunge. Never did that option tempt me even for a second, but my fifteen-year-old son declared his intention to jump the second he heard about it. We had failed to bring bathing suits to Antarctica, but his workout clothes would suffice.

Swathed in the bathrobe from his cabin, Jack made his way down the ship’s main staircase, escorted by his proud sister until he had to continue to the landing deck alone. We rushed to the viewing deck, craning over the water, and awaited the moment of truth. Would he turn back? Would this cautious child of mine who had foiled the efforts of four swimming instructors, who had refused to learn to swim until my father pushed him into the deep end — would he think better of this madness? Jack stepped from the ship onto the zodiac launched for the occasion, standing tall and steeled for his adventure. The crew fitted him with a lifeline — so they could fish out the guests in the event of shock or heart attack — and he stepped onto the side of the pitching rubber boat. Without a moment’s hesitation, Jack cannonballed into the Antarctic Ocean while everyone on the ship cheered his acrobatics. Never have I seen that child move so quickly as he swam to the ladder and pulled himself out of the 1º water into the 0º air, smiling at the congratulatory crew with a frozen grimace.

We the paparazzi met him on the stairs, amazed at our responsible first-born who had done something outrageous — what would he do next? — and asked him what it was like. His first word was: “Salty!” I thought the frigid water may have slowed his thinking — Yes, son, oceans are salty. But a trusty scientist explained that the Southern Ocean near the Antarctic coastline where icebergs form is significantly saltier than other oceans! When the water freezes, it pushes the salt out of the ice, back into the surrounding water, making the Polar Plunge a bit stingy for chapped lips.

Accustomed now to the daily adventures — well-padded by safety precautions — I experienced no qualms when the crew decided to go ahead with a zodiac tour of the towering cliffs around Spert Island, in spite of the choppy water. Our raft was driven by a young Brazilian woman from the expedition crew — a cute twenty-something historian — who bounced us over the surf, jolting with each wave as we sped toward the magnificent rock formations. Famous for its natural arches and skyscraper cliffs, this volcanic island invited exploration — but a whole host of icebergs had floated in and blocked most of the points of entry to the labyrinthine interior. Our driver’s walkie-talkie crackled instructions: No matter, we would go around the island to the other side.

That decision involved a foray into the open water, and suddenly this exciting morning jaunt felt slightly more risky. Tension mounted as our driver fell silent, focusing all her brain power on the task at hand. Our prow rose and dipped, the sides pitched and fell with the waves, and we all grasped the safety rope and widened our feet on the floor to spread our weight. We tipped back and forth as we fell behind our buddy-zodiac that disappeared around the cliff forming the head of the island. Our driver’s walkie-talkie crackled again, and she responded quite audibly, “I’m coming — this is my first time driving one of these!”

That information was sobering. The surrounding water, deep enough for whales to pass under our craft, suddenly seemed unfathomable as I began to calculate how many minutes it would take for hypothermia to set in after a whale overturned us before our buddy could come to our rescue. There was no question of drowning — we each wore sleek, high-tech life preservers that would spring into action upon contact with the water. Nor did being eaten by a killer whale concern me — I didn’t imagine they were interested in us. No, the question was of freezing to death in the water — I had seen Titanic.

The ten passengers on the raft all looked at one another as we pitched and rolled on the choppy sea — Muslims from Dubai, Hindus from Mumbai, and Christians from Atlanta — all united by a sense that this boat ride was not fun anymore. Our normally chatty driver continued to fight the waves with an increasingly morbid silence. I might have become genuinely afraid had I not looked at my husband, who is never afraid. He wore a look of mild annoyance at our driver’s inexperience, and another glance around the boat confirmed that the thing closest to death here was the driver’s satisfaction rating.

Catching sight of a blue light emanating from a distant iceberg, I felt inspired to distract the group. Renewing my grip with one hand, I pointed with enthusiasm to the gorgeous formation and said, “There at two o’clock! Look at the incredible blue light coming from that iceberg! Even on a cloudy day, it looks like it’s being lit from within!” I really did say it in that affected way, and truly, it was magnificent — one of those miracles of light refraction that if you’d seen it in a movie, you’d say it was fake. The feint had its effect on me, as well as the others — everyone turned to focus on the light, and no one looked annoyed anymore. Our driver corrected her steering, and we seemed to cooperate with the waves instead of fighting them as we made our way around the cliff to the relative calm of the far side of the island.

Sadly, the waterways even on the far side were blocked, but we were able to sneak between two cliffs and have a view of the interior before the turning tide exceeded our driver’s limited comfort zone, and we had to turn back anyway. I remember thinking on the return ride that I’d had enough adventure for one day and would unapologetically enjoy my re-embarkation hot chocolate.

The glaciers creep

Like snakes that watch their prey, from their far fountains,

Slow rolling on; there, many a precipice

Frost and the Sun in scorn of mortal power

Have pil'd: dome, pyramid, and pinnacle,

A city of death, distinct with many a tower

And wall impregnable of beaming ice.

Yet not a city, but a flood of ruin

Is there, that from the boundaries of the sky

Rolls its perpetual stream.

–from “Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1816)

Writing before the discovery of Antarctica in 1820, Shelley expressed his awe at the deadly power of an Alpine glacier. His words recurred to me as I rode through Antarctica’s Iceberg Graveyard on our last day, grateful for the genius who had envisioned this landscape before mortal eyes had seen it. Called a graveyard because the continental current grounds the icebergs on the ocean floor in these shallow waters, Pleneau Bay is where icebergs go to die. So we were told, but during our zodiac tour around, behind and between these magnificent palaces of ice, far from seeing a “city of death,” I witnessed a timeless endurance.

The flat surface of one ice floe ten feet above our heads held tremendous blocks of ice the size of industrial threshers, lying helter-skelter as if dropped there by a giant’s toddler. In the distance, pointing toward the sky in complete isolation, a monolith of ice stood like Saruman’s Tower. Another iceberg graced with two arches emitted a soft blue light, while yet another held a dark cave with an imposing arch guarding it.

There were formations like sinking ships and gargantuan sea monsters, baby dragons and giants’ faces. And though the grounded icebergs would last only ten years in the lapping water and evaporative air, the snow that had compressed into that ice — which formed the glaciers from which those icebergs had broken free — fell more than fifteen thousand years ago. What has this scenery been doing for all that time with no one to see it?

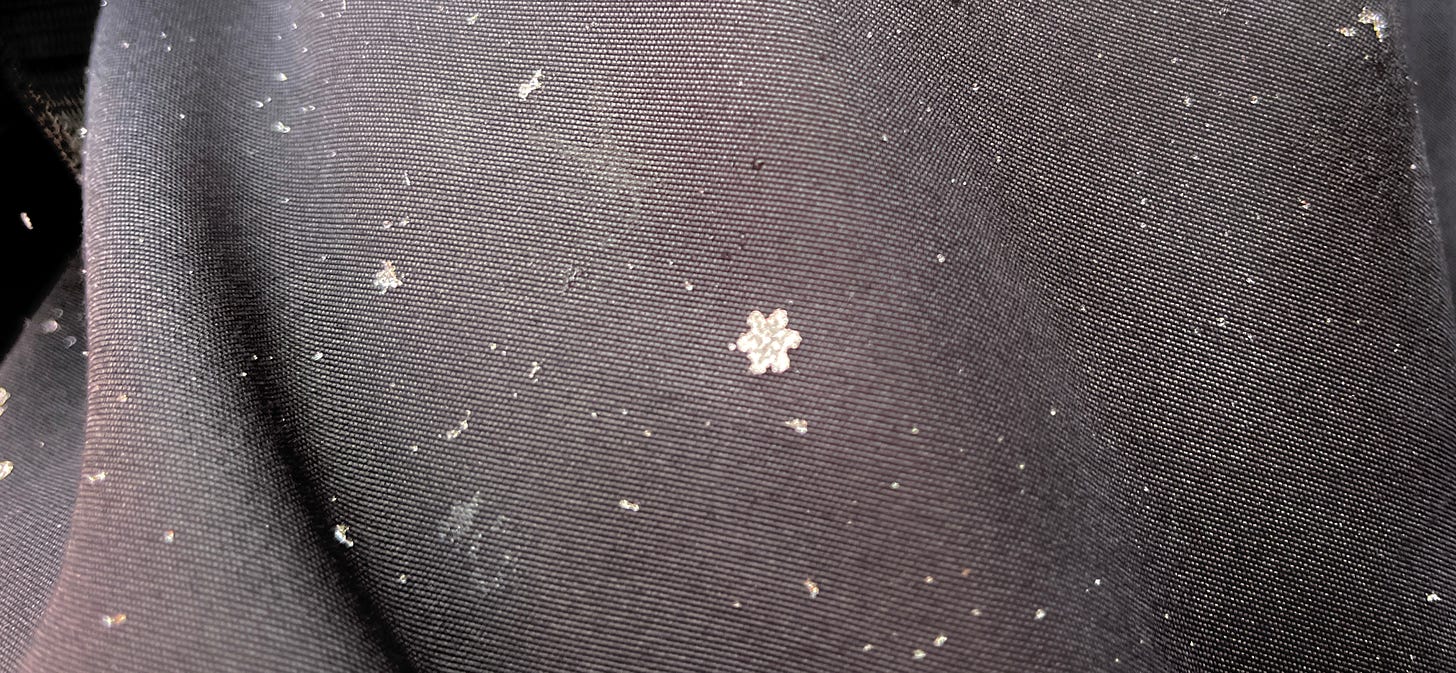

In the expectant quiet, we floated among these creations from another eon — when suddenly snow began to fall in the Antarctic desert, recipient of only a few inches per year. The sight was magical. My son — introspective by nature and tired, perhaps, of the sixth day of icebergs — watched the flakes land on his pant leg. “Look!” he said, pointing at a little flake, preserved in the freezing cold and shining on the black fabric. There, ¼ inch in diameter, lay a perfect snowflake, as if cut by a Christmas elf. I have seen pictures of individual flakes before and knew they were hexagonal and crystalline in shape and that each one is unique, etc. — but never in real life have I seen a snowflake-shaped snowflake. And they were everywhere — perfection all around, resting on every surface.

From the monumental to the minuscule, from the Paleolithic to the present moment, this landscape — existing, ever changing, for millennia without our observation or appreciation — has struck me with its purpose. It’s shouting something whether we’re there to hear it or not. Percy Shelley interpreted his Alpine glacier’s cry when he wrote in “Mont Blanc,” “Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal/ Large codes of fraud and woe” — in other words, to proclaim that wrong will be made right — good news to a broken world. Eighteen hundred years before Shelley, the Gospel writer Luke recorded Jesus of Nazareth’s translation of Nature’s cry. Jesus had enraged the Pharisees per usual when he not only refused to silence his followers, worshiping him in the streets, but also declared that even Nature itself would identify him as the Good News: “I tell you, if these [people] were silent, the very rocks would cry out.”

In Antarctica, they already do.

Amazing. Love the photos and thoughts along the way.

Brilliant travelogue. I loved the bookends of Coleridge and Shelley (Rime of the Ancient Mariner is a long time favorite of mine). What an amazing trip. Thanks for allowing us to take part!