After reading my recent essay about my deceased mother-in-law (which you can find here), my mother said she shuddered to think what I would write about her after she’s dead. But I say, why wait? After all, the author Julian Barnes said to write as if your parents were already dead.

There’s such rich material to be mined in the deep intimacy of the parent-child relationship. Nobody’s parents are perfect — we all have something to complain about, and I sometimes wonder what aspects of my parenting will pay the mortgages of my children’s future therapists. But since my parents were outstanding, it would be churlish of me to harp on their faults. Besides which, it’s much more fun to talk about my own foibles — and blame them.

The main word that comes to mind when I think of my parents is: Perfect. Not because they were perfect. (Oh, yeah — they’re not dead yet.) It’s because of this: my dad has a stock response to the innocent query, “How are you?”

He always says, “Perfect!”

If you’re new, this reply is a conversation starter, which is his intention. If you’re an acquaintance who’s heard it dozens of times, it’s a joke that you anticipate. If you’re his daughter, you’re sick of it.

What he means by his unusual reply is something like, “Things could always be worse — I’ve got nothing to complain about.” Or, “My problems pale in comparison with some people’s — they’re not worth talking about.” It’s also an expression of his faith, as in: “God is taking care of it — I’ve got nothing to worry about.”

But what I hear when my dad says he’s perfect is: “I don’t want to be real with you.” (Because — to be clear — he’s not actually perfect.)

My dad and I have always had a warm relationship. He was a fantastic father growing up — as close to perfect as one could hope for in this broken world — so what I see as arms-length treatment has been a bit hurtful. I’ve told him this point-blank many times: that I want to hear how he’s actually doing — that being in a relationship means telling me the good news and the bad. But he continued to respond “Perfect” — so I didn’t call him for six months.

He didn’t take the hint. Being the great dad he is, he kept checking in to see how I was doing. He may have been “perfect,” but I wasn’t. I had no qualms complaining to him — he got an earful.

Stuff like: “My tire picked up another nail, and I have to get it patched again.”

Or: “The pool has turned green, and we’re going to have to replace the pump, if you can believe it.”

You know — important stuff. But when I asked my dad how he was doing when he called each week, he was still “Perfect.” Did he think he was teaching me something? That all my little first-world problems were actually blessings? Message received, thanks!

“Now, how are you doing, Dad? Don’t say you’re perfect!”

“Perfect!”

Arrgh!

While my father continued to claim perfection, my mother had a different history with the word. She recently commented that perfection was a theme in the lives of many ladies of her generation, raised by the revered folks who proved that hard work wins world wars. The standard of good behavior was very high, perhaps particularly for those, like my mom, who grew up in the Bible Belt. In addition to the pressure applied by judgy matrons, my grandfather’s profession added another layer. He was an ordained Baptist minister and a professor of Greek and Hebrew at a Christian university where my grandmother also taught piano pedagogy. Their Christianity was professional as well as personal, and their only child needed to reflect the dedication with which they practiced their faith.

As a result, my mother was a very good child. She became a very good teenager and survived to become a very good adult. My peers often told me as a child that I had the perfect mom. She was always available, though never hovering. Sweet and patient, she never lost her temper. My disobedience made her sad, not angry — so I learned to behave relatively well out of sheer gratitude. Only a terrible person would thoughtlessly make that woman cry.

Therefore, I also learned to hide the worst of my crimes. I had an irritating little brother 5 ½ years my junior who provoked me beyond my endurance (it’s undeniable, Peter). To put the little stinker in his place, I resorted to a variety of devilish plots. In the Car Capers, I would pinch him in the back seat to make him scream — and get him into trouble. In the Suitcase Suppressions, I’d zip him up into luggage and leave him howling — until I switched roles and became the hero, releasing and comforting him in the Luggage Liberation. In the Dastardly Deaths, I’d pretend to pass out and play dead to make him cry — though why he would be sad about my demise was a mystery, given how terribly I treated him.

My poor mother was bewildered by the unrest in her home. As an only child, she had never experienced sibling rivalry and never had to share anything growing up. She couldn’t stand the acrimony and roused herself and my father to combat it.

To begin this campaign, my Dad sat me down and explained how my brother was always going to be my brother, and that long after he and my mom were gone, my brother would still be my family — my best friend if I treated him like we were on the same team instead of enemies.

After that, my mother increased her vigilance and allowed not one moment of sibling unkindness. The idea that sibling rivalry is normal and should be expected was banished from our home. We had to encourage and speak kindly to each other, and anything less would be disciplined. Thanks to my mom and dad’s aggressive parenting, my brother and I became great friends. (It helps that he forgave me for the Suitcase Suppressions.) (I think. We don’t really talk about it.)

Given my parents’ masterful training, I thought that I would be the perfect mom and reign over a peaceful household. I imagined I would have four stair-step children — two boys and two girls — who would respond with cheerful obedience to my benevolent dictatorship. Imagine my shock as I watched my two toddlers succumb to the same traps as every sibling since Cain and Abel — and yes, it looked like it would end in murder.

The fault for the sibling violence was mine. Well, mine and God’s because my son Jack is circus-tall (6’7” at 16 years of age) and has been abnormally large from the beginning, which is not my fault. It’s very difficult to discipline a two-year-old who is larger than the average four-year-old. I believed in spanking (it worked on me), but you try wrangling a 50 lb. toddler! I never could spank hard enough for him to care; “Time Out” was utterly useless for some reason; and — gulp — I never exerted the necessary effort to discover how to discipline him. The result was this: my son learned at age 2 that his size was intimidating, and he became a preschool bully.

His most famous crime occurred the day I received a call — from the delightful Miss Paige at the Heiskell Preschool — informing me that my two-year-old son was undergoing discipline for a remarkable act of bullying that she had never before witnessed. With barely concealed hilarity, she described the incident wherein Jack had entered the room and seen a fellow classmate in his chair. Jack was furious that she had taken his seat — so he grabbed her under the arms, lifted her from the chair, and threw her across the room. The child was airborne and thankfully landed on some cardboard building blocks. In spite of the obviously inappropriate use of his superpowers, the little girl was fine, thank goodness. It turned out that it wasn’t even Jack’s chair.

At that time, I was at home with my newborn baby girl India and harbored concerns about Jack’s future treatment of her. My fears were well-founded as Jack — equally possessive of my attention as he had been of his chair — proceeded to repress his sister at every opportunity. He was tired of her within the first five minutes of their acquaintance, and though he had learned he couldn’t throw people, there were many other ways of asserting his supremacy.

As India grew (and Jack continued to outsize everyone), his favorite form of suppression was sitting on her, though hitting was a second favorite. My little girl would scream piteously and I would run from the kitchen to find Jack the Giant comfortably seated on her back with one hand pressing her face into the floor. I was strongly reminded of the Suitcase Suppressions. Could it be that my diabolical tendencies had passed genetically to my son?

Indeed they had. Forewarned is forearmed. I kept an eye on that kid. I could barely leave them alone for 2 minutes before the screaming would start. He spent hours in Time Out, to no avail, and I began to have visions of his ending up in jail. And then India turned four, and the brew became even more toxic.

No match for Jack physically, India had to develop a different weapon. She cultivated a rapier wit — a poisoned tongue that would zing Jack whenever she thought I was out of earshot. The fault lines became more complicated. True, Jack must not pummel her no matter what, but India was provoking him. Perhaps the joy of seeing him punished was worth inciting his wrath. There’s no telling who began this new war to the death, but my home was a battlefield — and India was learning the extent of her verbal power.

Words could manipulate, as well as hurt. With the adults in her life, she discovered the trick of getting her own way. “First-time obedience” was a myth that never became reality in my home. She successfully delayed or avoided obedience altogether by distracting me every time I told her to do something. A typical scene occurred as follows:

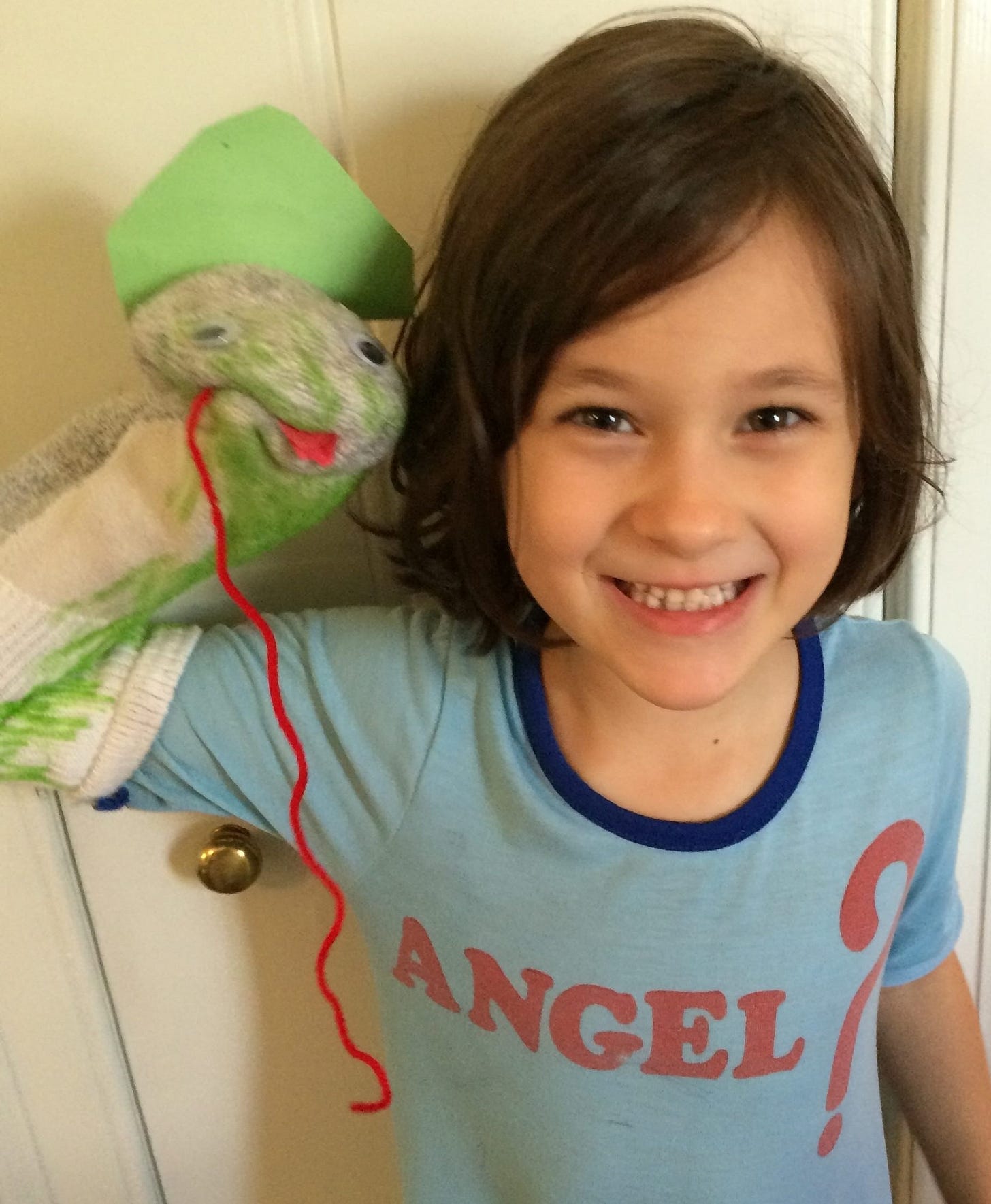

“India, it’s time to clean all this up. Put everything away, please.”

“Mommy, look what I made!” [Shows me several sock puppets.]

“Oh, honey, those are adorable!”

“Will you watch the show?” [Points to the colorful puppet stage she has created from Amazon boxes.]

[I check my watch.] “Yes, I’d love to see it, honey!”

[India performs the sock-puppet show, which is — remarkably — very funny.]

“That was great, sweetheart!” [I check my watch again.] “Oh, it’s time to go! You’ll have to clean this up when we get back.”

[The mess sits there for three days because I forget to follow through and India has no intention of cleaning it up. In the end, it’s just easier to put everything away myself because she has moved on to the next project, which I don’t want to interrupt, believing that I’m encouraging her creative abilities — which I am doing, but I’m also teaching her that creative people should be messy, rebellious, and irresponsible, an idea that I vigorously reject. (If only I’d rejected it vigorously enough to make her obey.)]

Kind reader, lest you believe my daughter behaved better in public than she did at home, that hope was shattered during a Pre-K parent-teacher conference at Redeemer Day School with Miss Pat (mother of Miss Paige, incidentally). Miss Pat said with gravitas that 4-year-old India was extremely smart and had hoodwinked me. Miss Pat described the daily scenes at school in which India performed the same bait and switch she had perfected at home, charming the adult into admiring some creation of hers, thereby avoiding the pesky instructions that she didn’t like. Miss Pat said that I had failed to discipline this child, and that if I did not remedy the situation in the narrowing window available to me, India’s life would become a self-centered disaster — and it would be my fault.

There I sat, hunched on that little preschool chair across from Miss Pat, and cried. She offered some encouraging words about God’s grace being sufficient for me — but they did not immediately penetrate my fog of failure. I was a thirty-six-year-old woman with two Ivy League degrees whose maniacal perfectionism was focused on the full-time rearing of two obedient children of excellent character — and faced the evidence that I had widely missed the mark. Jack had learned to get his way through tyranny and India through trickery. I had created a Mussolini and a Machiavelli at war with each other — what was I going to do now? How had I fallen so short of the perfect parenting I’d envisioned?

In concert with my husband Kirk, I channeled the spirit of my parents, remembering that sibling rivalry was unacceptable, and delivered long lectures to the children about love and forgiveness after every explosive fight. (You can imagine the effectiveness of that.) Nothing changed for years except that my housekeeping got worse — who has time to clean when you’re constantly parenting? — and I became a raving harpy, screaming at my children who had long outworn my last nerve.

During this epic battle, Kirk and I attempted to unite the troops by homeschooling Jack for first and second grade with India tagging along. I love learning and thrilled at the perfect picture of midweek museum visits and midyear family trips with my children trailing after me joyfully, à la the Von Trapp family. As Julie Andrews, I would teach them about Napoleon while visiting Waterloo, the Mayans while admiring Chichén-Itzá, the pagan gods while climbing Mount Olympus, all while singing the Greek alphabet in rounds of contrapuntal harmony: “Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon!”

It was a fiasco. My failure to discipline my son had led to him not respecting anything I said, and he was unteachable — by me, anyway.

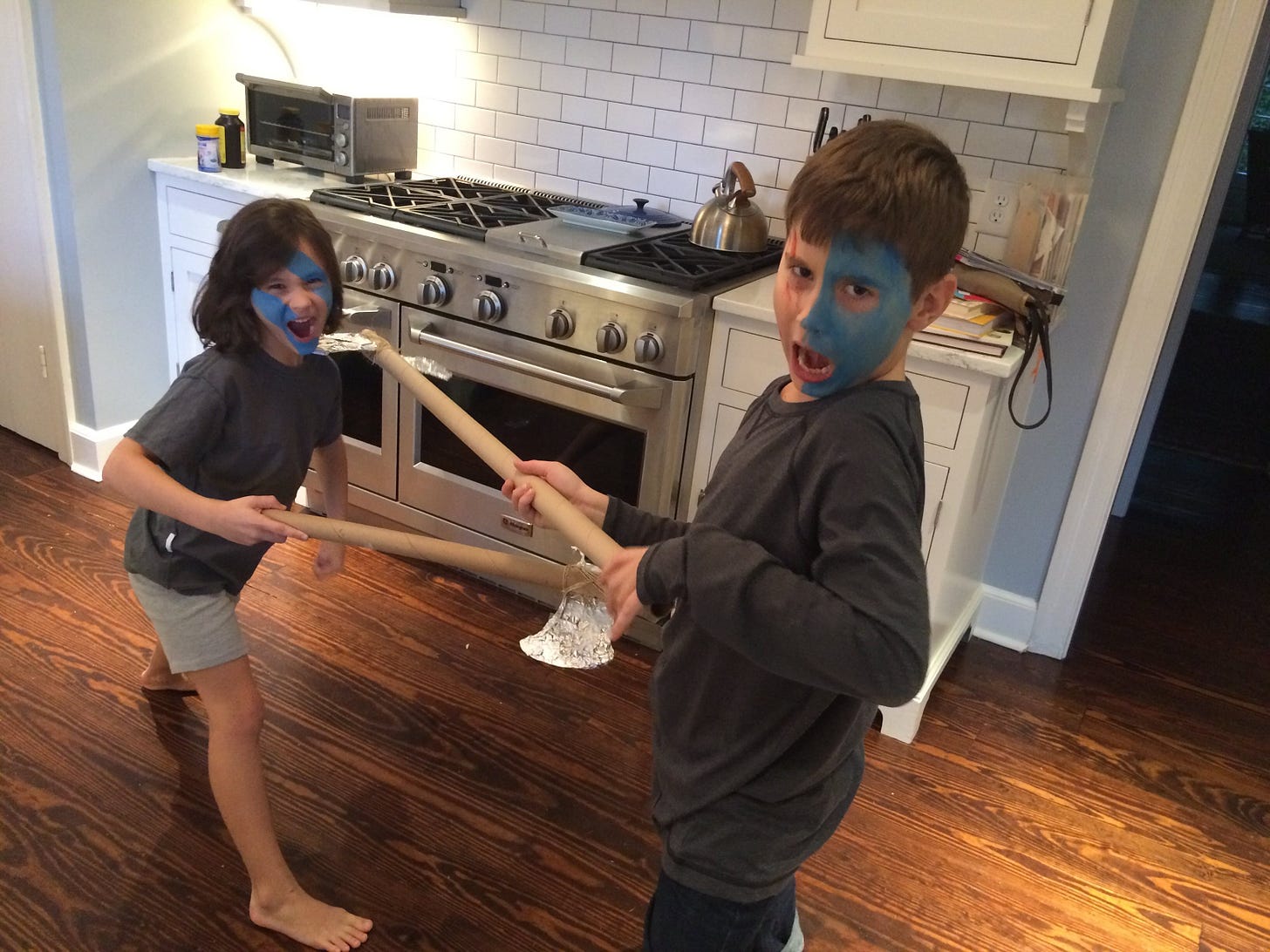

Not that I didn’t try. Yes, we mummified a chicken when we studied Ancient Egypt. Yes, we made Cuneiform clay tablets when we studied the Sumerians. Yes, we made battle axes and had a Celtic battle in the kitchen.

And, of course, for Halloween, we dressed as characters from books we’d read.

These are the highlights I cling to as evidence that the educational experiment was not a complete failure. But I taught my dear son not one good study habit, his handwriting degraded into a scribble instead of improving, I began to get migraines every day — and the children’s acrimony was ever-increasing.

It became clear that I was not a perfect parent — I was a pushover. Desperate, my husband and I put them both into Heritage Preparatory School, a classical Christian school in Midtown Atlanta, and let the teachers deal with the fallout of my disastrous mothering. (Bless you, Kat Stewart.)

In the spirit of “All we can do now is pray,” I joined a group of mothers at the school who had started a weekly meeting called Moms in Prayer. We prayed for the teachers, administrators, and children at the school and spent some time each week praying for our own children. After several months of scattered prayer asking the gamut of blessings from more self-confidence to better sleep, I finally settled on the main issue: I prayed that they would love and forgive each other.

And behold, God waved His magic wand, and Jack and India suddenly began to behave perfectly, encouraging each other cheerfully, obeying me immediately, speaking respectfully.

Actually, no — nothing changed. In the ensuing months, my home remained a combat zone with India’s sniping and Jack’s wrenching things from her. (He had graduated from Pounding Her Person to Taking her Toys.) Family vacations were a waste of time and money because we spent each waking moment arbitrating this Iliadic battle and imposing sanctions to punish their crimes. Everyone was losing this war of attrition.

Until four years later, all at once, God did wave his magic wand — and everything began to change.

They were 12 and 10 years old at the kitchen table doing homework, and India said something nasty to Jack about his handwriting. I took a breath to correct her before he took justice into his own hands. And then I saw something happen.

It was supernatural. Praying those desperate prayers had been like watering a sapling every week for years while ravenous for its fruit. And then in one moment, in the winter of our discontent, the tree sprouted full-grown apples.

Jack stopped everything and didn’t kick her under the table, didn’t grab her pencils from her, didn’t take revenge. Not only that, he then said,

“Yeah, I guess you’re right, India. My handwriting is terrible.”

I looked at India to see if she had witnessed the same miracle, and her expression melted as she watched him. Normally, he would have punched her arm; instead — wait for it — his humility pierced her heart.

She teared up as she realized the unkindness of her words and said, “I’m sorry, Jack! I shouldn’t have said that. I didn’t mean it.”

“That’s ok, India,” Jack said. He leaned over and gave her a half-hug, and India held onto him with adoration. And then they both went back to work.

I stood there with a knife in my hand, mid-way through a chicken thigh, and felt like I’d glimpsed the perfect world beyond the veil of this one. This scene of sibling harmony showed what we were supposed to be: not defensive about our weaknesses, but humble about them, knowing that our worth rests on something else. Heck, I had even witnessed what forgiveness was supposed to look like: not gouging out an eye for an eye (or pretending that losing your eye is fine). It means confining the darkness to yourself because your light comes from somewhere else.

Naturally, I can’t tell you that they behaved perfectly after that — India’s quick tongue and Jack’s iron fist often overcame their fledgling self-control — but apologies came quickly, which is the best sign of change. These days, India controls her tongue (most of the time), and Jack limits his despotism to parenting her when he thinks my husband and I are falling down on the job.

The greatest news is this: in spite of my inconsistency in disciplining my children, God has worked a miracle, and now they are best friends — an answer to prayer beyond any reasonable hope. The preschool bully has disappeared, replaced by Jack the Gentle Giant, Defender of the Small. A first-born tyranny of perfectionism seems to plague him, but he’s on the way to accepting that there’s only one perfect person — and he is not it. And India has learned that Clever Burns are not a fruit of the Spirit — she is more careful with her words. She still occasionally takes advantage of my persuadability to get her way, but I have hope that I’ll grow a backbone before she graduates from high school. It’s a longshot, but that’s the nature of God’s grace — it is undeserved and does more than we ask or imagine.

Now what about my dad, Mr. Perfect? I still want to know what he’s thinking, how he’s feeling, what he’s doing, and I don’t want to hear that he’s perfect anymore. (This is your take-home point, Dad.)

But at the end of this story, I’m inclined to appreciate his assessment of his life. He just turned 75 and, in the past three years, has survived three health crises that should have killed him.

First, by divine intervention alone, three 85-100% blocked arteries were discovered by a timely EKG — three days before he would have died running the Peachtree Road Race. Within 24 hours, he had a triple bypass without ever suffering a heart attack.

Second, after recovering from open heart surgery, he suddenly developed a severe allergy to a medication he’d been taking for 8 years, which evolved into sepsis from which he nearly died.

Finally, the powerful antibiotics and steroids that stopped the sepsis caused a corrosive ulcer in his duodenum that ate its way into an artery, causing him to lose 50% of the blood in his body in the span of thirty seconds. (You don’t want to know more.) Thank goodness he hadn’t felt well and had arrived at the ER just in time. His life was spared for the third time — and he knows that his “perfection,” hard work, and virtue didn’t save him.

This humbling lesson has been driven home to me, too — through my parenting experiences. I can look at my mess and pretend I’m wily enough to straighten it out — or I can admit my insufficiency, rely on Jesus’ perfection, and live in the hope that God’s grace is sufficient for me; that God’s power is made perfect in weakness, as Paul says in a mic drop from 2 Corinthians 12:9.

That’s what my dad has chosen to do. So when you see him next, be sure to ask him how he’s doing. He’s living in hope, and he means it:

He’s Perfect.

Anita, that's hilarious! Did I use a fresh tissue for each of them? Or did I spread their germs all the way down the line? Thank you for your kind words -- and for teaching me about Jesus at 2 years of age.

It delights a parent’s heart to see our children grow to be good friends. There will be many hard times ahead (life is hard), and reminders of our dependence on the Lord’s strength when we’re too weak to help (2 Cor 12:9), so never stop praying for them.