Is Anything Worse Than Contemporary American Politics?

Yes: the Holocaust. Our Summer Trip to Auschwitz

Dear Readers,

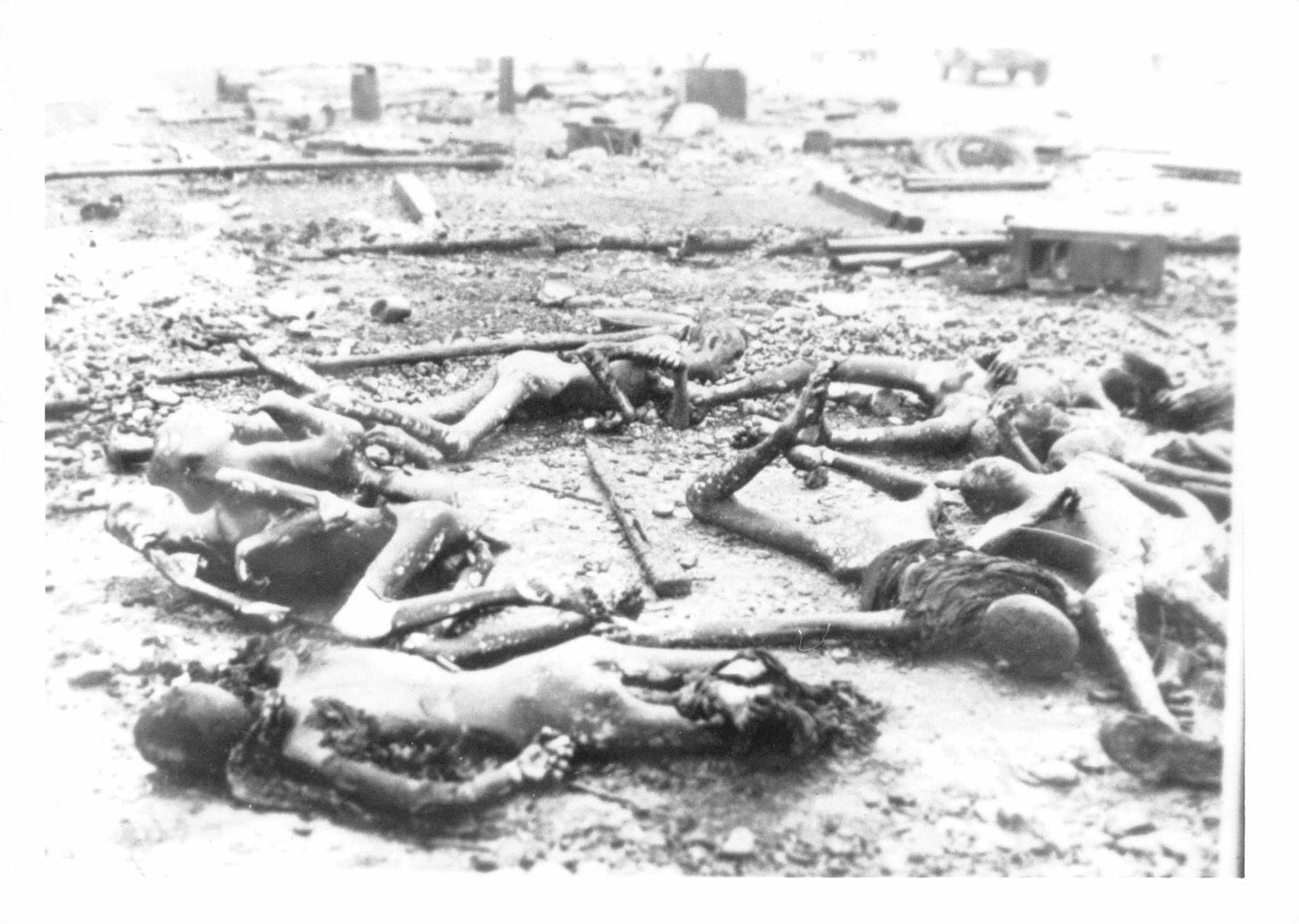

This month’s post requires a word of caution as it includes a few of my grandfather’s pictures from the concentration camp his division liberated at the end of World War II. The photos are graphic, and I don’t want you to come upon them unaware. Now you know, and I hope you’ll enjoy this essay.

Is Anything Worse Than Contemporary American Politics?

Yes: the Holocaust. Our Summer Trip to Auschwitz

“Don’t try to make the Holocaust funny.” This was my mother’s advice when I told her the subject of this month’s essay. She thinks I lack reverence for certain sacred topics — like my dearly departed mother-in-law, my children’s privacy, and Jimmy Carter. Certainly, there is nothing funny about the Holocaust — quite the contrary — but you might join me in seeing if there’s anything new to be said about that seminal tragedy.

I had some nervousness while planning this visit to Auschwitz with my family. My kids have studied the Holocaust in school and knew that six million Jews had been killed during the Second World War — but even the way I just typed those words so easily shows how removed I am from the horror. Would my children be properly disturbed when seeing evidence of the atrocities? Or have they played too many shoot-em-up video games? An even scarier question: how many times will I type the word atrocities in this essay? Has my sensitivity to atrocity become as stale as that word?

I kind of felt like I’d seen it all. My first exposure to the Holocaust was the year I turned nine when I visited Dachau, a concentration camp in Germany. I was traveling with a group of violin students through the German-speaking countries, performing concerts in various venues — and Dachau was on the itinerary. (We did not perform there.) I remember my morbid curiosity as I peered at the photos, enlarged for the exhibit, and counted the dead bodies. The more gruesome the pictures, the more mesmerizing. I recall maintaining a studied expression of sadness so that no one would see how riveted I was by the nakedness of the dead bodies in one photo.

I remember various rooms in which there were mountains of shoes and piles of spectacles and heaps of clothes — all that remained of the murdered — all very drab and dull in a 1940s kind of way. It was somber and confusing — how does one capture the magnitude of six million murders? How can a nine-year-old understand it? I remember the commemorative wall that displayed these words in four different languages: “Never Again.” I had become one of the people who must perpetuate the memory of something terrible — what was it, precisely?

My grandfather was with us on that Germany trip, and he knew — he had been a U.S. Army chaplain in World War II, and his division had come upon Nordhausen concentration camp at the end of the war when liberating that part of Germany. As a chaplain, my grandfather did not carry a gun, so with his free hands, he was instructed to wield a camera and document the horrors they discovered as they liberated the camp. The images he captured are now in the archives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. I include some of them below, but please proceed carefully. They are shocking.

Can you imagine seeing these things for the first time? These soldiers had not seen Schindler’s List. These sights had never been witnessed by anyone living in the free world. No one had been desensitized. We want to believe such things can’t be real. But my grandfather saw them and captured it all on film — and as he and I walked together through the museum at Dachau in 1987, I remember watching to see how the museum photos affected him. Would he cry? Would he have a meltdown? What were his feelings on seeing it all again?

I will never know my grandfather’s thoughts at Dachau upon seeing these things again because my nine-year-old self failed to ask him. He did not burst into tears or lose his composure. As a theologian and an ordained Christian minister, he was familiar with the concept of sin and had spent 40 years weighing the Nazi’s actions. Interestingly, it has now been nearly 40 years since I visited my first concentration camp, too — and I wonder how that early exposure has affected my perspective.

I visited another Holocaust museum in 1994 when I was 16 years old. My family drove to D.C. to do the national monuments thing — and visited the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which had just opened the previous year. Once again, I put on my solemn face and remembered not to smile for pictures as we walked through that impressive exhibit. Again, there were the mountains of shoes and piles of spectacles and heaps of clothes — much better displayed than the Dachau ones — and again, the photos of starving prisoners and dead bodies. There was a miniature polystyrene model of the gas chambers, showing the interior with its attached crematorium, and little plastic people filling the floorspace to show the scale. This Holocaust museum succeeded in making the incomprehensible slaughter more personal. Upon entering, every visitor received a card with the description of a real person from history. This card anchored me in the overwhelming flood of information. Knowing that this devastation didn’t happen only to an anonymous six million Jews but also to one particular Jewish girl my age brought the Holocaust a bit nearer. This time, those pictures of the dead could have been my mother or brother or the boy I had a crush on. It was particularly sobering to learn that the girl on my card did not survive the war — she died at Auschwitz.

Auschwitz has reentered the cultural conversation this year. The 2024 Academy Award for Best International Feature Film went to The Zone of Interest — the story of the notorious commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess. Every day during the war, he walked home from the death camp to his wife and children playing in the yard — without any discussion of the atrocities (there it is) being committed a few yards from their door. In the film, Auschwitz is deliberately, flagrantly absent — suggested only by the rising smoke of the nearby crematorium, the barbed wire above the garden wall, the occasional gun shot, the chugging of trains, and the faraway screams of unseen victims, all ignored by the family as they swim in their pool and relax in their beautiful garden. They were so… normal — and this strange juxtaposition of normalcy with systematic murder prompted our family’s curious summer vacation.

We stayed in Krakow, Poland, one city which miraculously survived both the war and the Soviets with its historic buildings intact — and has the largest medieval square in Europe, incidentally. One day, our lunch on the square was punctuated by a loud pro-Palestinian protest with bullhorns and drums. Young Polish students with green and purple hair marched around the square waving Palestinian flags and carrying posters with Israel’s Star of David crossed out in red. No doubt they would have described themselves as anti-Zionists, not anti-Semites, yet I couldn’t help but consider our upcoming visit to Auschwitz — one of the places of horror that inspired the United Nations to support Israel’s foundation in the first place. Did these students ever ponder the historical echoes? Hitler promised in his Reichstag speech that the coming war would yield "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" — and indeed, 90% of Polish Jews were killed by the Nazis. Now, Hamas promises in its Covenant "to fight the Jews and kill them" or to die trying — and on October 7 of 2023, they successfully undertook jihad, a war that has no end. Many Poles bravely resisted the Nazis; others collaborated. Where would these students have fallen?

The next morning, we drove to Auschwitz, about two hours away. My worry that I wouldn’t have the proper reverence about this visit was soon justified as I began to worry that my morning pastry wouldn’t last me through lunch. I wondered aloud if there might be a restaurant at the museum where I could get food — and received an incredulous look from my husband. A vision of people dining at Auschwitz seemed like a scene from a surrealist black comedy — I banished the thought.

We met our Polish guide Barbara outside the museum on the sidewalk, and she led us through the hordes of fellow-tourists queuing to enter. The brand-new visitors’ center was completed within the last year and effectively prepared us for the emotional bleakness we would shortly experience. Unadorned concrete walls and bare counters confirmed there would be no restaurant (the error of my thinking was confirmed), but I was grateful for the discreet vending machine out of the way near the restrooms. It was filled with American snacks, and I felt more prepared after a Snicker’s bar. As I munched, I mused that every tragic story I was about to hear was framed in the knowledge that the Allies had won the Second World War and the Cold War, defeating Fascism and Communism, and that I was a blessed recipient of that freedom — all represented by one Snicker’s bar in a former death camp.

Barbara led us out of the visitor’s center toward Auschwitz and told us in her lightly accented English that she was from there. From where? I asked, feeling that something had been lost in translation. You can’t be from a concentration camp. But in a sense, she was. Barbara had grown up in the Polish town of Oświęcim, which the Nazis rearticulated as “Auschwitz” so they could more easily route people to the correct death camp. I cannot imagine a worse place to hail from.

The sky should have been dark or depressing for this visit, but the weather did not cooperate. It was a sunny and beautiful day with insensitive birds chirping as we walked toward the front gate of Auschwitz over which the famous words read, “Arbeit Macht Frei” — Work Sets You Free. Barbara said that was a 19th century slogan employed by the German government after World War I to encourage the people to greater productivity and prosperity. Had the Germans felt the unendurable pressure of that slogan and weaponized it in their Nazi slave-labor camps for that reason?

Barbara gave us a comprehensive history of the area, which I will give you here in brief. As she began to talk, I noticed the preposterous signage of a pizza restaurant peeking over the adjacent trees and turned my back to it in order to focus on these important points:

Auschwitz was the first of three major concentration camps in that area called the Zone of Interest.

The Zone of Interest was a forty-square-kilometer sector controlled by the S.S. that also contained officer housing, farmland, and the factories and labor pits in which the prisoners worked.

Most importantly, the Zone of Interest provided a buffer that would prevent the Polish people from knowing the extent of the Nazis’ crimes.

Auschwitz I, which we would shortly enter, had originally been the barracks for the Polish Army and became a ready-made concentration camp.

When the Nazis began the Final Solution to kill all the Jews, they razed the nearby villages in the Zone of Interest and built Birkenau (Auschwitz II), the main death camp that we would tour later.

Now you’re caught up.

Barbara led us at a determined pace from the front gate, past the execution yard to the two-story brick barracks where the prisoners slept twelve to a bunk built for three — and where the people’s ghostly remains are now displayed. For the third time in my life, I confronted the familiar mountains of shoes and piles of spectacles and heaps of clothes. And there was the same miniature polystyrene model of the gas chamber/crematorium, as if they had been mass produced. (20% off if you buy five!) But I was relieved to find that my familiarity did not breed contempt — on the contrary, the exhibit rekindled my memory about something my nine-year-old and 16-year-old self had considered. An answer was forming as to why it’s important to rehearse all of this, and what I’m supposed to know…. That the Holocaust is a unique event in human history? That racism is the root of all evil? What narrative do these Holocaust memorializers want me to preserve?

The tragic remains were presented without drama or fanfare. A mountain of hair, cut from the murdered victims and saved to make rope and mattress stuffing, rested eerily behind a 30-foot glass wall, filling half the room — mostly dark brown and black tresses, some blonde, many gray. In another room, a tumbled pile of suitcases reached far above our heads, many with the owners’ names still chalked on the sides — because when they were led to the “showers”-cum-gas-chambers, they’d been told they would need to find their belongings later. Another room contained a vast pit filled with the pots and pans and kettles and cups that the deportees had carried on their long journey, hoping they would settle somewhere else. Half of another room contained thousands of shoes collected from the victims: muddy and worn from their owners’ ordeal. The ones with holes had shod the poor; a smart red pump had adorned the rich — and I couldn’t help but think of Ecclesiastes 9:2.

It is the same for all since the same event happens to the righteous and the wicked, to the good and the evil, to the clean and the unclean, to him who sacrifices and to him who does not sacrifice.

As we left the museum barrack, we passed more looking just like the others — but these barracks had special significance. Barbara referred to these as “Canada.”

“Like the country?” I asked, imagining that our hapless North American neighbors were somehow POWs in this terrible place.

Yes, but not to house people, she said. The deportees had brought their most precious possessions with them sewn into their hems and packed in their bags that they carried across Europe. After they were killed, their belongings were sorted and stored in these barracks where the Nazi officers and their wives could go shopping — for a new dress to wear to a party; for a new pair of shoes for their children; for a replacement pot for the stove; or for almost anything else you could want. These barracks were a source of plenty during the war, and the prisoners and soldiers alike compared it to the fabled wealth of North America — and called it ‘Canada.’ (Maybe Canada was more prosperous than America in the 1940s? I was too embarrassed to ask why it hadn’t been called ‘America.’ But unreflective enough to think that it should have been.)

We followed Barbara at her dogged pace past the remaining barracks, through the double, 13 foot-tall fences of barbed wire, to the gas chamber. I tried to ignore my rising discomfort by focusing on her relentless information: There were originally five gas chambers in the combined Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp complex. But as the Russians encroached on Poland at the end of the war, the Nazis destroyed the four largest gas chambers and crematoria at the nearby Birkenau camp, presumably to destroy the evidence. If the Nazis were so desperate to hide their crimes, I asked myself, they must have known they were wrong… right?

Pointing to this remaining gas chamber, Barbara said that because they were using it as a bomb shelter when the Russians arrived, the Nazis failed to destroy it — leaving us with the evidence. She opened the door to the gas chamber, which was built under a hill such that the door seemed to lead into an ancient barrow. I felt a wave of panic as she disappeared inside that dark grave where so many thousands had been murdered. We followed her into the gloom, and as our eyes adjusted to the dim electric bulbs, my first thought was: It’s huge.

Low ceilings made the gas effective, and the enormous floor space could fit several hundred people at a time, said Barbara. This gas chamber was the smallest of the five — at Birkenau, each chamber could kill over 2,000 people at once. Used twice per day, the five chambers enabled the Nazis to murder approximately 20,000 Jews per day at the height of the Final Solution.

We scuttled back into the sunlight and took a deep breath. After two hours of this, it was high time for a break. Barbara said she’d meet us at the entrance to Birkenau, just a five minute drive away and left us to make our way through the Auschwitz bookshop. (No souvenirs or gifts, thank goodness. Can you imagine an Auschwitz fridge magnet?)

We drove through the modern residential neighborhoods that have developed in the Zone of Interest on our way to Birkenau. Nearly there, we came upon an unexpected sight: the golden arches of a McDonald’s. Its bright facade seemed like the final defeat of Nazi and Soviet control of this depressed area. This was the nicest-looking business I’d seen around, and I speculated that the locals must value their cheap and abundant American calories — and, hopefully, the freedom they represent.

We pulled up to Birkenau and saw the iconic entrance to the camp with its train tracks running through the gatehouse to its grim destination. My husband captured the picture below on our walk through 150 yards of a scraggly field to the entrance. We showed our security tickets from Auschwitz, walked through the gate — and then I had trouble processing the magnitude of what I was seeing.

While the army barracks of Auschwitz were cloistered and even claustrophobic, Birkenau consisted of vast fields extending in all directions.

The scale of the Nazi’s operation was breathtaking. This enormous camp existed for the purpose of selecting deportees either for hard labor or death. Upon arrival, the trains would disgorge thousands of prisoners onto the half-mile-long platform where the Nazis would immediately divide them by gender. The doctors would then either select them to work and receive the famous numbered tattoo or would send them straight to the gas chambers. 80% of arrivals, the gross majority of whom were Jews, were immediately murdered without ever being registered.

All the surrounding land behind the barbed wire fences had housed the slave laborers until they died of overwork or disease and were replaced. At first, I had thought the fields were empty — but then I saw hundreds of chimneys spaced like trees in an orchard, each a ghostly remnant of a prisoners’ barrack. Their lumber had been taken by the returning refugees after the war — and only the chimneys remained like forefingers raised in warning.

The train tracks stretched half a mile into the distance toward two clusters of rubble: the exploded gas chambers and crematoria. When we reached the ruins, there wasn’t much to see other than piles of concrete collapsed into subterranean rooms — but the train tracks told the tale: they came to an abrupt end between the ruins, the train’s final destination and the literal end-of-the-line for 1.1 million victims.

Hearing the stories and witnessing the evidence was exhausting. How much review of the Nazis’ depravity do we need in order to remember it? What was my takeaway from all this? That Nazis are bad?

On our way back to the gatehouse, we attempted to lighten the conversation by asking Barbara her story. We knew she had grown up in the town of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) within walking distance of the death camp — but didn’t know that she has led two tours a day, several days a week for most of her adult life. She leads the English-speaking tours because speaking of these things in her native language makes her cry. Before the war, her grandparents had owned a farm in the Zone of Interest from which the Germans evicted them in 1940 to use as officers’ quarters; and during the war, they lived outside the Zone in a small house with five other families. Her grandmother had snuck food into the Zone of Interest where she knew prisoners were starving — but was unaware of the extent of the evil, Barbara was careful to note. In her emotionless English, Barbara described how her grandmother, at great risk to her life, would hide potatoes in the mud of the labor pits where the starving workers could find them.

In spite of her Polish family’s innocence — and even their heroism — during the war, it seemed like Barbara had a debt to pay. The way she rattled off statistic after chilling statistic on our three hour odyssey through the two camps seemed like the performance of a Sisyphean task she must forever repeat. One of the many lowering details she shared gave me a hint of the burden she carried: during the war, the S.S. sold fertilizer made of human bone meal to local farmers, simultaneously enriching and cursing the soil. Barbara had grown up playing in the dirt and eating the food from the soil and swimming in the river fed by the ashes of 1.1 million murdered victims. The crimes committed in her town, though nearly 80 years old, live on in the trees and the fruit they produce. What justice could possibly atone for these abominations?

After VE Day in 1945, the Nuremberg Trials brought the captured Nazi officers to justice in a kind of atonement. My grandfather was friends with another American chaplain who had a pass to the trials and gave it to my grandfather for a few days. In Papa’s letters home to my grandmother that week, he wrote something important. He said that the Nazis all looked so “normal.” They were just dads and husbands and accountants and engineers and salesmen — and looked just like he did. My grandfather didn’t write this to excuse any of them for their heinous acts. On the contrary, he noted their normalcy as if it were an indictment of himself. What evil lurked beneath his own, normal exterior, ignored by himself because of its familiarity?

Almost two decades later in 1963, the writer and philosopher Hannah Arendt hinted at something similar in her controversial book about Adolf Eichmann’s belated trial as a Nazi war criminal. Its subtitle reads: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Though Arendt did not practice any faith and used different words than I, she saw Eichmann’s sin for what it was: universal, pervasive, familiar, normal. Though the Nazis perpetrated incredible evil, their violence sprang from the same petty and trite instincts shared by the rest of us — and there is a Final Solution for every degree of sin from antisemitism to xenophobia.

“The wages of sin is death,” wrote the Jewish man named Paul to the early church in Rome 2,000 years ago. Being a banal sinner like everyone else, I’m on that inexorable train track headed straight for the eternal crematorium. But rather than consign all of us to the lake of fire, God’s Final Solution called for the death of only one man — the death of a Jew, actually. This death would be so torturous — and so entirely undeserved — that the immeasurable injustice of it would outweigh all our combined sins, great and small.

But there’s even better news about this Final Solution: it doesn’t end in that man’s ashes and our enslavement. In this Solution, the phrase Arbeit Macht Frei is true: work actually does set us free — but not our work. The work of one Jew’s perfect life, self-sacrificial death, and resurrection. His work sets us free: free from sin — and free from death. Nerd out with me for a moment: The German word for Resurrection is die Auferstehung, and it shows us what he accomplished. Auferstehen (to resurrect) comes from erster stehen, or “first to stand.” The ancient German word for “first” is ester, which became Ostern, the German word for Easter. On Easter, he stood up from the grave first so that anyone who believes that he did — will, too.

But many of us would rather not rely on someone else’s effort — we’d like to be good enough on our own. When I take so much pride in my work — in what I can accomplish, in who I am, in how I do it better than those people do — then I become the virtuous standard by which I measure everyone else. From there, it’s a short goose-step to comparing nose lengths and skin color; to wanting those people to live somewhere else; to wanting those people not to live; to wielding the power of life and death over them — because now my virtue makes me a god in my own eyes. (Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries is playing in my head right now as I write this.) Relying on my own excellence gives me the hubris to kill — whereas relying on Jesus’ excellence gives me the humility to forgive.

During 2024’s excruciating Presidential campaign, the temptation to brand our opponents as Nazis kept popping up. It’s the favorite insult for anyone we hate that we use in order to signal how much better we are. (Than Nazis? Congratulations.) No one in American politics today is like a Nazi — except in the sense… that we are all like Nazis, as my grandfather observed firsthand at Nuremberg. We all know that we’re better than some other group of people who should either see things the correct way or get out of the way. Every one of us has drawn a line of virtue that we’re on the correct side of — and been outraged by those idiots on the other side. (Whom did you vote for? I’m unsubscribing!) The fact that we Westerners are not killing our political opponents at the moment is not because we’re more virtuous than Hitler. Add a little starvation and bleak economic futures and watch us start blaming each other. (Who am I kidding? My children gave me a button pin in my stocking last Christmas that says, “Hell hath no fury like me when I’m slightly inconvenienced and hungry.”)

I think I can finally articulate what I’ve learned from all these visits to Holocaust museums, though it may not be the curators’ intended message. Because I believe I’m morally superior to Nazis, I’m in danger of making the same mistakes — of elevating myself as the standard instead of measuring myself by the actual standard. But there is a hope that’s more secure than my flawed efforts. I’m better off relying on Jesus’ work, which covers the failures of anyone who admits his own. Even repentant Nazis, thank goodness. Otherwise, what hope is there for me?

Thank you for writing this, Kate. This was hard to read- my rapidly increasing heartbeat can attest- but I am so grateful you did not leave us with the image of the grave. Thank you for pointing to the one who stood up out of the grave! And thank you for the sobering, but important, reminder that not a single one of us could be any better— There but for the grace of God go I.

Kate, well done! You expressed it all so beautifully. I am so very proud of you, friend!