A Time-Travelogue to Medieval London with Excursions to Modernity for Tea

Voyage 3: Medieval Faith and Churches

Experience Voyages 1 and 2 here:

Voyage 1: 1348, The Year of the Black Death

Voyage 2: The Black Death Cemetery

Voyage 3: Medieval Faith and Churches

Tuesday is my last day in London, and I make the most of it, diving into the Middle Ages by touring the City churches. Medieval life thrummed with the reverberations of church bells, marking the rhythm of daily life. In my novel, I want to capture the ethos of a world that lived by faith — before the humanism of the Renaissance turned our gaze inward; before the rationalism of the Enlightenment gave us faith in what we could measure; before the overload of the Information Age made us like gods, self-defining and all-knowing. In my tour of churches today, I hope to capture threads of this bygone era and weave them into the thoughts and conversations of my characters. My mother gave me a book about all the churches in the City of London, and I research every one of them, whittling them down to the few that have medieval remains. So much was lost in the Great Fire and so much more in the Blitz. But there are a few medieval sprinklings left to collect.

On my way south through the City to the Thames, I pass St. Mary Aldermary, which has no medieval remains that I know of but has been converted into a charming cafe since no one worships there anymore. I stop for a pot of tea while finishing my new book on London’s medieval gates. It’s unsettling to be in a magnificent place of worship, clearly built for the glory of God, that now stands like a beautiful shell left on the shore of England as the tide of faith pulls away.

“The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.”

— Excerpt from “Dover Beach,” by Matthew Arnold (1867)

After finishing my book, I plod through the cold down to Lower Thames Street near London Bridge to St. Magnus the Martyr. The porch of this church used to lead directly onto the original London bridge, famous for falling down. (The new London Bridge spans the Thames about 150 feet upstream of the original location.) There’s nothing left from the medieval period — but the church is home to a miniature model of London Bridge as it would have looked in 1400, an essential visit for a hopeful-medievalist.

Seeing the medieval bridge as it would have been during the plague brought some poetry to mind:

“Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.”— The Wasteland, by T.S. Eliot (1922)

I walk east along the Thames and quickly reach All-Hallows-by-the-Tower (of London, that is), which has a Roman and medieval crypt. The bombs of the Blitz gutted the church and revealed this forgotten crypt, along with many interesting artifacts — such as Roman oil lamps, coins, iron styli for writing in clay, and a beautiful key. Things like these will be familiar to my medieval proto-archaeologist whose digging discovers bits of London’s Roman past only a few feet under the soil.

I strike north, leaving the Thames and the Tower of London behind me, and stop into St. Margaret Pattens, named in honor of the patten-makers that lived nearby in the Middle Ages. Pattens were medieval rain boots — essentially wooden platforms or iron hoops that one would strap onto shoes, thereby raising one’s feet above the dung and mire. They were worn into the 19th century until rubber boots surpassed them in popularity. They will have to make an appearance in my book.

I swing by St. Olave on Hart Street — famously Samuel Pepys’ place of worship with a churchyard gate that Charles Dickens dubbed “St. Ghastly Grim.” You can see why. It seems to be an active church and advertises lunchtime concerts — but I’ve never caught it open to visitors. The current structure is not medieval, so I shake the dust from my feet and move on.

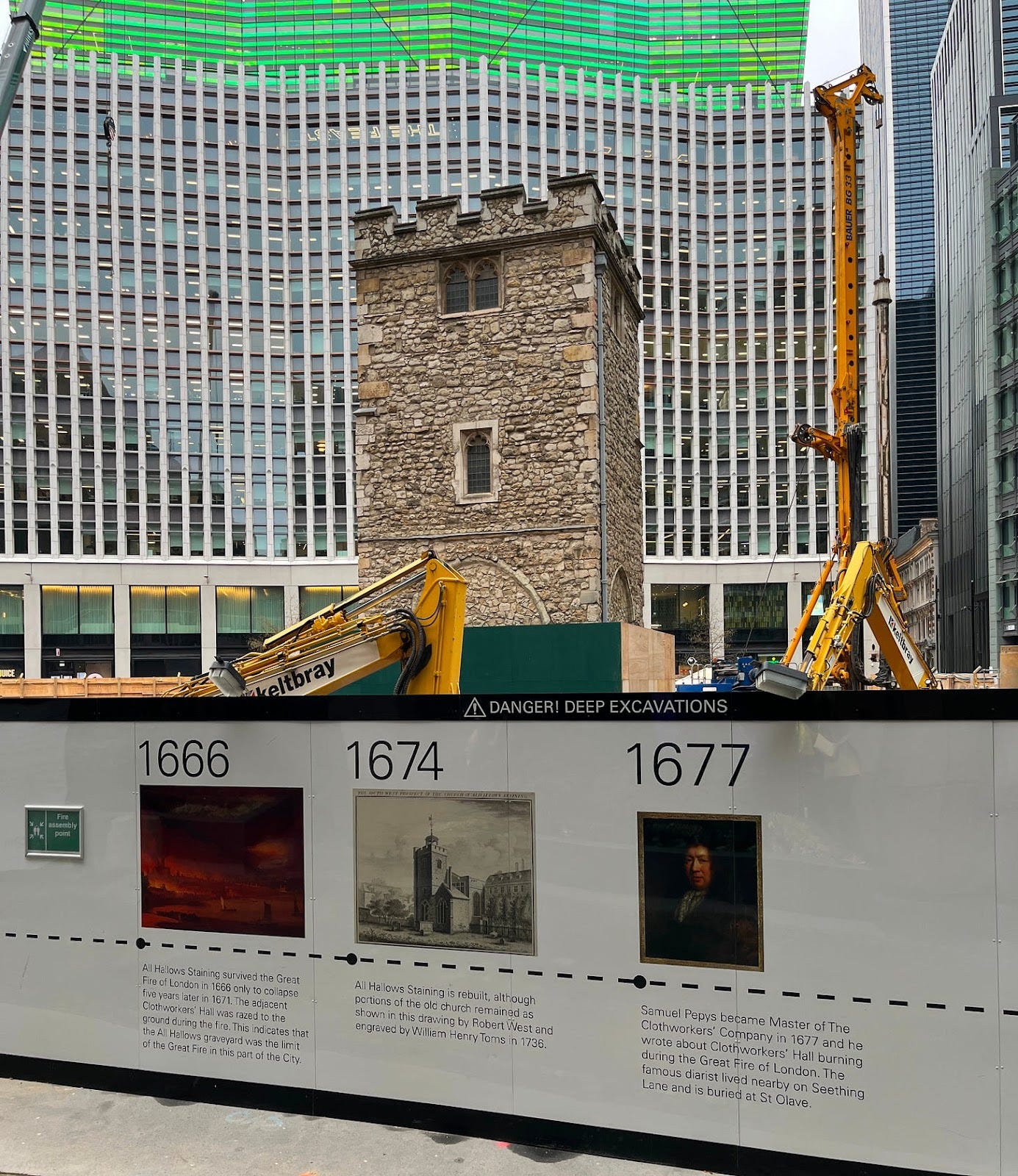

Time collapsed — and the City has swallowed — All Hallows Staining (meaning built of stone instead of wood to differentiate from the other Saxon “All Hallows” churches). This remaining medieval tower is protected by law and will be incorporated into the garden of this development. Can you imagine how this church was surrounded by thatched wooden houses in the 14th century?

As the light begins to fail, there still remains a smattering of churches with medieval connections along the northeastern trail of the London Wall. I stop by each to feel the distance between them — all so close in this crowded City-within-the-Wall. The last of this grouping gives me a startling glimpse into the past. It’s called All-Hallows-on-the-Wall, literally built into the London Wall, a portion of which remains at this location.

The current church building is 18th century, but the medieval London Wall forms part of its foundation and is still visible. This is the strange part: from the 13th century through the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, it was somewhat common for churches to have a structure attached to the outside that housed one “anchorite” after another — mostly women — who requested permission from their Bishop literally to wall themselves into the cell. All-Hallows-on-the-Wall had such a structure built into the Wall in which people “anchored” themselves to that place and separated themselves from the temptations of the world. Such ascetics lived on charity or their families who would bring them food, and they never emerged from their cells — ever. Their lives were devoted to prayer. From what I’ve read, this seems to have been a respected choice showing great piety.1

I stand for a long time outside this church looking at the Wall and try to imagine a person living in a hovel — not from necessity or from failure or from insanity, but — from utter devotion to her God. My modern mind wonders about hygiene — which shows how far removed I am from the concerns of a 14th century anchorite. Who in 14th century England had hygiene? According to church documents, the anchorite who lived here around the time of the Plague was named Margaret Burre. I think she must make an appearance in my novel. I also wonder if she discovered the uncomfortable truth in her cell, protected from all worldly temptation, that sin doesn’t come from without — but from within. Did she know Latin — or Greek? Before an English translation, could she have read Jesus’ words that said,

“What comes out of a person is what defiles him. For from within, out of the heart of man, come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, coveting, wickedness, deceit, sensuality, envy, slander, pride, foolishness. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a person.”

— Mark 7:20-23 (English Standard Version, 2001)

I would never choose to be locked in a cell alone with that list of evils — and without 21st century sanitation.

Twilight descends, obscuring the distinction between past and present, and I scurry towards home. My way lies along the London Wall, nonexistent for this stretch, remembered only in the street name (literally “London Wall”), which runs into the Barbican as it did almost 2,000 years ago. The Romans had a fortified outpost here (barbacana), which was reinforced by the medieval mayors defending the City in the War of the Roses. Crumbling remnants of those structures remain. The Luftwaffe flattened this area, destroying the warren of timbered houses and shops, wrecking the area of Cripplegate beyond repair. The post-war reconstruction committee decided that the best they could do for the city was to create a fortress-like housing and cultural development in the Brutalist style — that looks like the set for a post-apocalyptic blockbuster. I am one of the haters of this grim development, which some have argued is the greatest piece of urban architecture of post-war Britain. Reasonable people can disagree.

Miraculously, a medieval church — St. Giles-without-Cripplegate — survived the bombing (though gutted by fire and heavily restored) and stands today, a welcome relief from the Brutalist reminder of war that surrounds it.

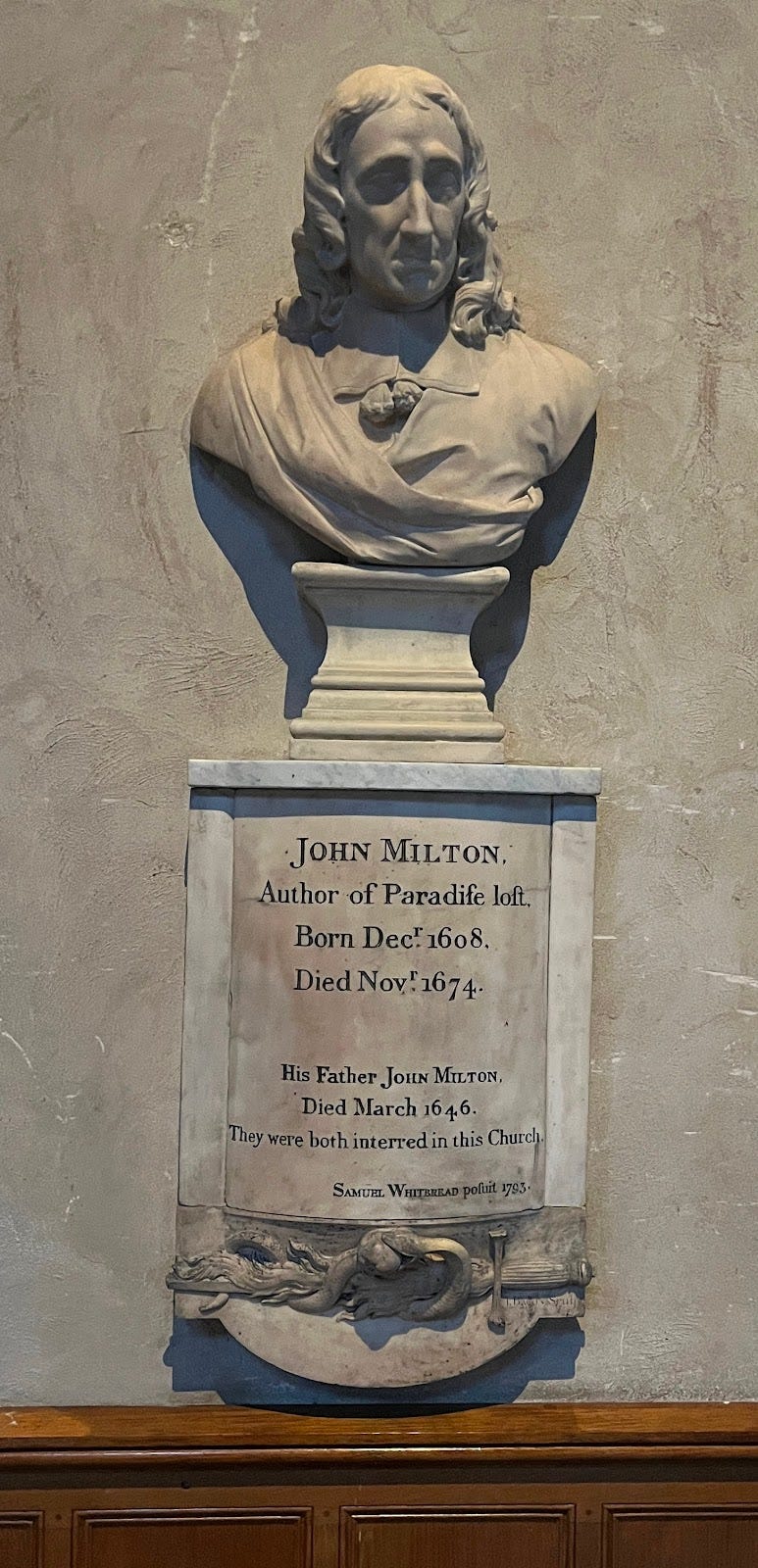

Incidentally, St. Giles is John Milton’s burial place, and his memorial plaque survives, as well.

In the trick of the half-light as I follow the remaining London Wall away from the Barbican, I am caught between-times in a palimpsest of ages. In a moment, I see Roman, Medieval, Early-Modern, Pre-War, Post-War — and seem to be out-of-time, watching the eons collide.

Nearly home, I give a nod to St. Paul’s Cathedral — Christopher Wren’s magnificent replacement of the burned medieval church — and pass my church that meets at St. Botolph without Aldersgate. Outside the door is a sandwich board advertising lunchtime talks. It says, “Does life give you questions? Jesus has answers.” I ruminate on that statement as I turn north through Smithfield, past St. Bartholomew the Great, back to the little flat where I’m staying.

The cold stings my fingers as I fumble for the keys, my thoughts on all the churches and remains of churches I’ve seen this week. I wait for the elevator, banishing the cold with a shiver, and consider the way these various churches represent themselves to the public. I’m so accustomed to reading how Great Britain is a post-Christian country that much of what I saw this week fits into that narrative. St. Mary Aldermary is a cafe; St. Ethelberga of Bishopsgate is a “Centre for Reconciliation and Peace” and “sits at the intersection of climate and peace.” Other churches hold services — while advertising foremost their Christopher Wren architecture, their lunchtime concerts, their support of the climate, or their inclusiveness — with no mention, besides these, of who or what they worship.

I step onto the tiny elevator where the clang of the closing door reminds me of the anchorite self-contained in her squalid cell. I check my makeup on the back-wall mirror, grateful that the anchorite craze died out with the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The faith didn’t die, though. It survived the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, the fall of the Papal States — it outlasted the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the British Empire, and will outlive the American one, too, whether we become “Great Again” or not. God’s faithfulness does not depend on ours.

As I return to the the toasty flat and prepare my dinner, I remember why I have such affection for 900-year-old St. Bartholomew the Great (see Voyage 1). It’s not because I’m a student of architecture or a true medievalist (not yet, anyway!) — or because old things have value in themselves. I love the church because it’s a symbol of faith outlasting everything — of faith growing in spite of us.

Christianity is not dead in England. I remember the joy of my Sunday service at LCPC (from Voyage 2) and think of my visit to another City church today: St. Helen’s Bishopsgate. It was late in the afternoon, so I couldn’t see the famous interior of this double-barreled church with two separate doors to two separate naves.

One side was a parish church for the populace and the other side was added in AD 1280 for the nuns from the adjacent nunnery — so they didn’t have to mix with the commoners? That doesn’t seem very sisterly — let’s give them the benefit of the doubt. Whatever their reasons, the double church still stands today — with the dividing interior wall removed — and is home to a thriving congregation of believers.

They proclaim in their literature, “We are all about knowing Jesus and making him known.” Their website’s tagline: “One thing matters. Taking the time to listen to Jesus.” Online, they have a free resource library of over 12,000 talks, articles, Bible studies, and videos — all to equip people to know Jesus. This is why the beauty of St. Bartholomew the Great speaks to me — and why St. Helen’s of Bishopsgate may become a new favorite on my next visit: faith in the Triune God is not an artifact of the medieval past, but is alive — is omnieval, if I may use a new word — for all time.

“[We] were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ… by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast.”

— Ephesians 2:3-5,8-9

So many great thoughts here, Kate. Such good reminders and hope that faith will and does outlast us all. And again, it amazes me that one can visit London a handful of times and STILL have a growing to-do list. I'd love to see the model of the London Bridge. I did step into St. Mary Aldermary when I was there and had mixed emotions. Grateful that it is still standing and not torn down, saddened that it's true use has been hung on the wall like an old coat. I ventured into St. Paul's for the first time when I was in London last summer and was astounded at the sheer size! But will absolutely be stopping into St. Bartholomew and St. Helen's when I'm next across the pond!

Lovely, have never visited these medieval ages churches (except for the Templar!)

adjacent nunnery — so they didn’t have to mix with the commoners? That doesn’t seem very sisterly

Also, the nuns probably has a vow of silence and isolation therefore they must be separate from the populace.