A Time-Travelogue to Medieval London with Excursions to Modernity for Tea

Voyage 1: 1348, The Year of the Black Death

Dear Time-Travelers,

Thank you for joining me on this odyssey to medieval London in the name of research for my next novel. I’ve divided my travelogue into three mini-voyages — each should take 10 minutes or less. This is the first. Buckle up and enjoy!

Voyage 1: 1348, The Year of the Black Death

My favorite spot in London is hidden from the main road that passes it. A 30 minute walk northeast of Trafalgar Square and 30 minutes northwest of the Tower of London, it’s not the first stop for visitors seeing the sights. You might occasionally see a lone backpacker consulting her guidebook, scanning the numbers on the row of buildings in front of it, unable to find the almost-secret entrance. Even a friend who has lived in the city for 30 years told me she hasn’t yet made the pilgrimage to this Central London place of wonders.

The world has changed around it — Bubonic Plague has ravaged the city multiple times; Henry VIII hijacked the Reformation to become Supreme Head of the Church of England; the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed almost everything south of it, all the way to the Thames; zeppelins bombed the City in the First World War and the Luftwaffe in the Second — and still this place remains. How long I can elaborate without telling you what it is? Time for the reveal: it’s a church.

The parish church of St. Bartholomew the Great — founded in 1123 by King Henry I’s jester, Rahere — is a portal to another world. It was built on Smithfield (or “smooth field” from the Saxon), a flat place just outside the London Wall.1 When Rahere lay dying from illness, he prayed for healing and made a promise. He would build a priory to God’s glory — and when God healed him, Rahere was true to his word. He founded this monastic church on an empty site that St. Bartholomew specified in a vision.

Bartholomew should have been the patron saint of real estate, but in fact he blesses many other trades such as bookbinding, leather-working, plastering, and butchery. Appropriately, traders began selling livestock at Smithfield outside St. Bartholomew’s doors in 1174 — and it has remained the meat market for London even to this day, blessed by St. Bartholomew, obviously.2

The field outside the church doors also hosted other butcheries: William Wallace (a.k.a. “Braveheart”) was drawn and quartered there in 1305; Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants’ Revolt, was beheaded there in 1381; and dozens of religious dissenters have been burned at the stake on what is now a park over a subterranean parking deck.

The original, street-front doorways of St. Bartholomew the Great have disappeared over time — except one. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s,3 Henry VIII evicted the monks and sold this priory as a country house to his friend Lord Rich. (Yes, really.) The nave — the long part of the church where the congregation would, well, congregate — was demolished and has been replaced by apartment and office buildings with expensive restaurants on the ground floor. Between a Michelin-Starred French restaurant and a wine bar, there is a curious half-timbered, Tudor house over a Gothic stone arch (one of the original doorways) — and that is the invitation for further exploration.

A paved walkway leads in a gentle downward slope between the buildings and then behind them to this quiet church, cut off from the traffic and the young world. The path descends past the churchyard with its mossy tombstones — and declines through the centuries to what would have been street-level 900 years ago when the foundations were laid. The adjacent cemetery has been layered with centuries of the dead and lies behind a retaining wall, its current tombstones as high as the church’s Gothic-arched door.

I arrive on a Wednesday late-afternoon in January — when London begins to dim around 3:30 and is dark by 5:00 — and enter the first set of doors. The friendly parishioners who keep the church open for weekday visitors greet me and invite me to take my time. Time will stand still once the second doors are breached — I take a last lungful of 21st century air and plunge into the past.

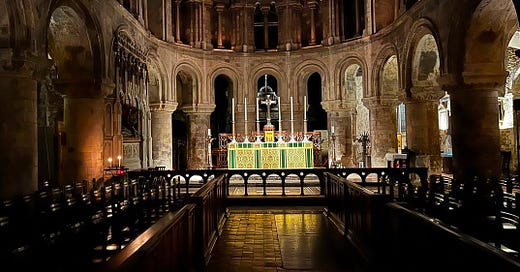

The church is dark but for electric lamps placed at intervals where candles or oil lamps may have illuminated the arches in the past. My next breath is full of spices. The incense from the Sunday service still lingers and reminds me how particularly welcome the fragrance would have been after the noxious smells of Smithfield’s offal, dung, blood, and unwashed bodies of previous centuries. The silence is reverent with only whispers from a few fellow time-travelers and the purposeful tap-tap-tap of a priest’s footsteps as he heads to his study.

The stones of the columns and arches are stained with the grime and soot of the last millennium and pitted as if from battle scars. Rahere began construction of St. Bartholomew following a near-fatal trip to Rome and brought back the prevailing architecture of the day — Romanesque, curved arches. But during the long construction, the popular style changed in favor of the Norman Gothic, so the architects pivoted and added pointed arches here and there, as well. The effect is disorienting — a hiccup in the time-warp.

I sit on a wooden chair in the empty congregation as the winter light strains through the glazing, so weakly that I can’t see the beams soaring overhead. A woman begins to turn out the lights — to aid some 21st century repair of an electrical board that is happening in that other time — and I am left in the medieval gloaming with a few devotional candles burning nearby. I have come here to soak up the past as I do research for my second novel, part of which will take place in 1348-49, the years the Great Pestilence (or, Black Death) wiped out half of London’s population. It’s a romance, of course.

The churches filled that year as many rushed to repent, hoping that God would spare them from this agonizing fate. As I sit in the twilit sanctuary, I imagine a priest reading the book of Job from the handwritten, illuminated Latin Bible in the pulpit. Would he have translated the scripture to English so his parishioners could have hope of resurrection in this crisis? Or did they derive some comfort from the Latin “hocus-pocus” (Hoc est corpus meum — “This is my body” — part of the Eucharistic Prayer) that they couldn’t decipher?

Scio enim quod redemptor meus vivit, et in novissimo die de terra surrecturus sum:et rursum circumdabor pelle mea, et in carne mea videbo Deum meum: quem visurus sum ego ipse, et oculi mei conspecturi sunt, et non alius: reposita est haec spes mea in sinu meo.

Iob 19:25-27 (Latin Vulgate, AD 404)

I know that my redeemer lives,

and that in the end he will stand on the earth.

And after my skin has been destroyed,

yet in my flesh I will see God;

I myself will see him

with my own eyes — I, and not another.

How my heart yearns within me!

Job 19:25-27 (New International Version, AD 1978)

Death surrounded those people every day when the infant mortality rate was over 40% and a man lived a long life if he died at 50 — but the Black Death was terrifying with its virulence. Excruciating pain coupled with the death of nearly 75% of those who fell ill communicated to them that God was very angry, indeed. Sitting in the 14th century, I can see the people kneeling around me, some sobbing in fear and repentance, others resigned to the will of God, whatever it may be. I wish I could capture this moment in time — but my phone has died at some point during the voyage, so I have no photographic proof.

Eventually, I become hungry for some 21st century dinner, so I quietly leave the dark sanctuary and its desperate parishioners, bundle up at the door, and tap my credit card on the conveniently placed donations terminal. £5 is a small price to pay for a trip through time.

The Next Voyages

Since time is precious — and an overflowing inbox devours it — the remaining voyages are linked below. You can also find them on katesusong.com if you prefer. Bon voyage!

Voyage 2: The Black Death Cemetery

Voyage 3: Medieval Faith and Churches

The Romans built this semi-circular Wall around AD 200, enclosing approximately 330 acres, bordered on the south by the Thames. King Alfred repaired it around AD 886, long after the Roman Empire had fallen. The Normans strengthened the Wall after William conquered England in 1066 — and the City continued to thrive within it for centuries. The Wall often saved London from attack during civil unrest and stopped the spread of the Great Fire in 1666. The City finally overflowed the London Wall during the economic boom of the 18th and 19th centuries when it fell into disrepair, was demolished bit by bit, and now remains only in protected sections.

After almost 900 years, the meat market will close in 2028. My favorite museum in London — the Museum of London — will move to the adjacent buildings, and the whole site will be redeveloped.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries was the event that many historians have called the end of England’s medieval period. In brief, the Reformation and Renaissance were in full swing on the Continent; in 1526, William Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament was the first English version to be mass produced on the printing press — making any Englishman his own priest as the word of God was now available to anyone who could afford a copy and read (boosting literacy dramatically) — and Henry VIII took advantage of the tumult to break with the pope, annul his unwanted marriage, and become “Supreme Head of the Church of England.” Gutsy.

A court jester building a house of worship to honor a promise would itself make a great story. Every knee shall bow and tongue confess that Jesus is Lord. Thanks for taking me on your journey.

Really enjoyed this, Kate. You might perhaps like this piece of mine. https://open.substack.com/pub/mathewlyons/p/the-poetry-of-steeples?r=210m2m&utm_medium=ios